A current popular opinion of world travelers is that one should get to Cuba before the unstoppable onslaught of Americans ruin the place. Calm down. Don’t be in such a hurry. Having just returned from a week in Havana I am pleased to report that I do not foretell American corporate presence and its ensuing aesthetic pollution, albeit conveniences, rushing in anytime soon.

I have come to Cuba under the auspices of professional research. On U.S. Visa paperwork I am sworn to engage in the study of the importance of the arts to Cuban culture. I am sworn to follow a full schedule of work activities and I am not to engage in activities solely for personal pleasure. My endeavor is genuine but the whole project exists in a gray area because fortunately my “work” is my passion. I shall keep a record of my activities and be ready to present such for U.S. immigration when I return to J.F.K.

From José Martí Airport, my driver drops me as instructed at an address I double-check because everything I see suggests the building in which I have a reservation to stay for a week is abandoned. I don’t realize it at the time but my American eyes are not accepting that in the absence of window decals, posters, neon, welcome mats, logos, water features, plant life etc. that an edifice can actually be functioning and legitimate. The locked lobby reinforces my confusion until an assumed vagrant motions for me to enter through the building’s rear.

A week of mind-opening contradictions begin as the elevator in the “abandoned” building opens to the Spanish-spoken welcome of two smiling grandmotherly ladies, the hostesses of my “Casa Particular”. It is as clean of an in-house lodging as I’d ever seen. A golden sunset sepias the shined terrazzo floors. The tops of Jetsonesque windows tilt outward. It’s as if I’m on the bridge of an aircraft carrier looking down upon the legendary seaside promenade called The Malecón. The building’s frame is rock solid concrete and the views take my breath. I’ve seen this classic seaside crescent before probably in old movies. I sit with my guitar and take a coffee expecting a song idea to come forth as is often the case in such moments of transitional repose but save for the beverage, I come up dry.

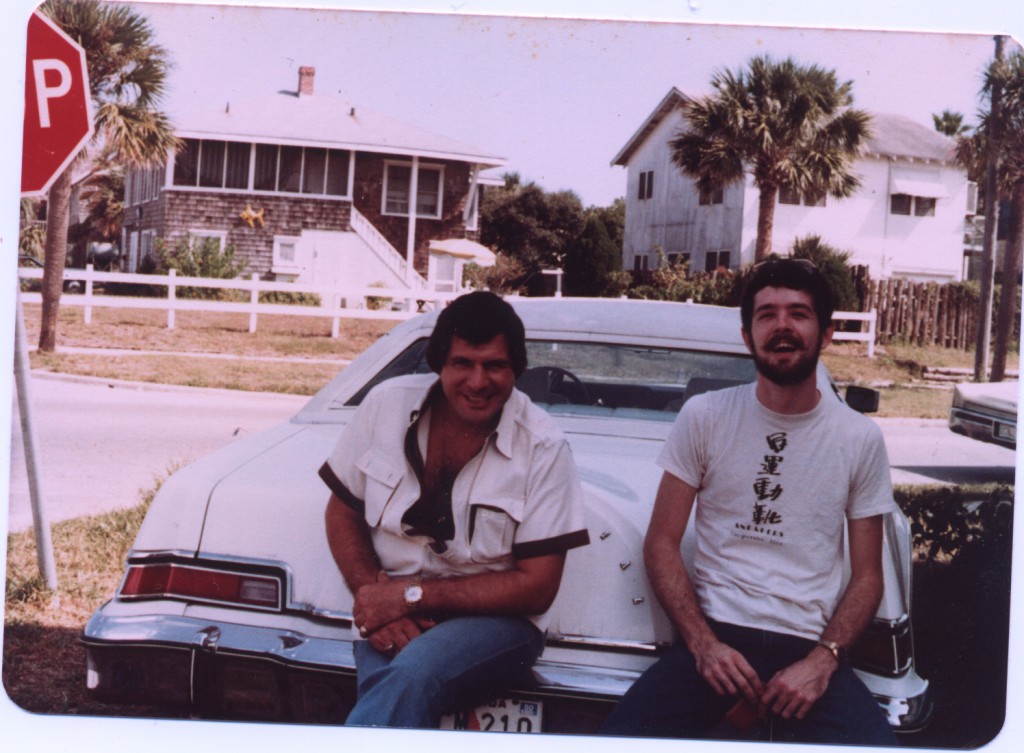

My brother initiates me with a nighttime stroll deep into old Havana which is in shambles. By dim light Habana Vieja seems like the ghost of a city and not a living one. The apocalyptic vibe is frightening and I ponder taking the next day’s first available flight out. A neighborhood in this condition in America would naturally be unsafe but I sense no threat probably because I can’t walk too far without seeing a policeman.

A rooster on a close rooftop, wakes me around 5:30 am. Two hours later my seventh floor advantage reveals both architectural beauty and deterioration in every thing I see. On neighboring buildings, the absence of original clay roof tiles has over time encouraged leaks, causing support beams to rot and ceilings to cave. I learn that even on floors with collapsed roofs, rooms with ceilings intact remained occupied. Spanning the entire Havana skyline, a single construction crane and many huge blue plastic roof top water tanks assure me that I have not gone back in time.

The March morning swelter becomes fully committed by around 10am. I’d like to avoid being perceived as the archetypical modern ugly American but I have chosen mid-century modern ugly American – a Batista era bright blue sport jacket over which I sling my guitar gig bag and hit the streets. I can’t walk a block without somebody shouting “Los Rollings!”. The Stones are in town and I somehow seem to be in the band. Given my 6’5” height I’m used to being a freak of nature but today in Havana I’m also a Stone. I attempt disclaimers to the contrary in my poor Spanish but people keep thanking me for coming. I am concerned that my pageantry will encourage begging but in my whole week’s stay only one person outright asks for help.

The common people (a term Cubans use) appear poor but with basics covered for they seem content and not desperate. They seem open to “holas” and brief conversation. The mansions in which they live are the spoils of the 1959 Cuban Revolution yet most all are deteriorating, albeit beautifully so, from 55 years of neglect. Without air conditioning, front doors remain wide open and the world peers through to watch them watch old tube televisions.

If I imagine these buildings in their glorious original condition I would compare the scene to Nice along the French Cote d’Azur. But sadly, rusted rebar has lost grip everywhere leaving balconies to collapse and remain unusable. There are no caution cones at the edge of gaping sidewalk holes into which the inattentive can fall. Having been raised by an architect, Old Havana creates in me a foundational level of anxiety that I will never shake during my weeklong visit.

to collapse and remain unusable. There are no caution cones at the edge of gaping sidewalk holes into which the inattentive can fall. Having been raised by an architect, Old Havana creates in me a foundational level of anxiety that I will never shake during my weeklong visit.

It’s not possible to capture all the chaos I perceive without keeping my cameras visible, locked and loaded but beyond my rather loud appearance I’m unwilling to becoming further the obnoxious tourista. A driver blows a tire. He stops where it pops right in the midst of traffic and takes his sweet time spinning lugs.  A merchant power pedals the dead weight of an entire gutted and skin-steamed pig that’s splayed on the bike’s rear cargo shelf. A man in a wife-beater tosses a live rooster by its legs into a car trunk. Somewhere I hear a lamb, en route no doubt, to its execution. I find it. Sadly its limbs are tied. It travels on its side on the floor of a tricycle-taxi, sort of thing. Stray mangy dogs miraculously avoid buses and taxis. I don’t know if I can handle this for an entire week.

A merchant power pedals the dead weight of an entire gutted and skin-steamed pig that’s splayed on the bike’s rear cargo shelf. A man in a wife-beater tosses a live rooster by its legs into a car trunk. Somewhere I hear a lamb, en route no doubt, to its execution. I find it. Sadly its limbs are tied. It travels on its side on the floor of a tricycle-taxi, sort of thing. Stray mangy dogs miraculously avoid buses and taxis. I don’t know if I can handle this for an entire week.

I was a young boy living in Florida during “The Cuban Missile Crisis” and as such my brain was thoroughly washed to view Castro as evil incarnate and “his” communism as a serious threat to the American way. It is impossible therefore to avoid an occasional knee-jerk prejudice while being here. Some aspects simply don’t make sense but I learn to keep government related curiosities to myself. In service to my mission I ask artists and museum guides questions about the importance of the arts to the Cuban government and to Cuban culture. Sadly the conversations are diverted or I get tumbleweeds. I quickly deduce that my research mission is mine to figure out by observation and by talking to foreigners who’ve been around for years.

When the Americans eventually come en masse I hope that they will appreciate the Cuban people for their industriousness rather than pity them for having to endure hardship. I’m hoping that Americans consider that making the best of what one has to work with was a necessary character quality in the folks who fled Great Britain and lay the groundwork for the country that we now call the United States. I feel a kinship with the guy who walks his broken bike taxi to the local welder to have him manufacture a part from scratch.  The whole scenario seems so primitive to my American eyes at first because the modification is immediate and is done right in the street, not in some fancy workshop. The final result is not pretty but it functions and allows for the wheels of Havana, quite literally, to keep turning. I too prefer to fix things rather than throw them away because I don’t like to be wasteful. Perhaps I waste time making modifications but I feel that a society composed of individuals who are unable to repair things is vulnerable. For sure, in Havana, a repurposing mentality is borne of necessity and is not the cute arty hipster fad that it is in the U.S. I see the fix-it process all over town and I’ve come to think that keeping things running is a strong component of Cuban pride.

The whole scenario seems so primitive to my American eyes at first because the modification is immediate and is done right in the street, not in some fancy workshop. The final result is not pretty but it functions and allows for the wheels of Havana, quite literally, to keep turning. I too prefer to fix things rather than throw them away because I don’t like to be wasteful. Perhaps I waste time making modifications but I feel that a society composed of individuals who are unable to repair things is vulnerable. For sure, in Havana, a repurposing mentality is borne of necessity and is not the cute arty hipster fad that it is in the U.S. I see the fix-it process all over town and I’ve come to think that keeping things running is a strong component of Cuban pride.

“You only carry a guitar around in this town if you’re good” says a cafe musician. Against my brother’s advice to not burden myself by traveling with my guitar, I find, as I had guessed I would, that by carrying my guitar everywhere, doors open for me. On my first thirty minutes along The Paseo del Prado, I am asked to sit-in with a hotel quintet fronted by three pretty females who synchronized dance moves while each holding down unique hand percussion duties. The band’s guitarist plays through a cheap amp yet his solos demonstrate a sophisticated jazz harmonic understanding. Because I used to listen to Cuban music years back in Florida I’m able to fill in parts that I don’t hear this band representing. I use the universal barometer of musician approval (a smile or lack thereof) to gauge how I’m doing. I deduce that playing my parts rhythmically correct seems to carry more weight than the actual notes played which I’m definitely fudging. My singing seems to be a pleasant surprise to the Cuban musicians and the bar manager asks me to stay for a while. From this spontaneous collaboration I observe that the Cuban government is obviously providing exceptional arts and music education because even in this tourist band, the musicianship is exceptional.

The jazz band at The Zorro y El Cuervo in Vedago reveled hard and focused. It’s as if a gig is a party that the Cub an musicians take very seriously. Over a cortadito in a cafe at the corner of The Malecón and Prado I enjoy hearing a simple trio of old Cuban men in customary white short sleeve pleated-front shirts playing old school boleros. They soothe in the spirit of The Buena Vista Social Club using merely the essentials – classical guitar, percussion and violin. I have issues with the popular opinion that Havana is a trip back in time but I must accept that this moment is one such trip.

an musicians take very seriously. Over a cortadito in a cafe at the corner of The Malecón and Prado I enjoy hearing a simple trio of old Cuban men in customary white short sleeve pleated-front shirts playing old school boleros. They soothe in the spirit of The Buena Vista Social Club using merely the essentials – classical guitar, percussion and violin. I have issues with the popular opinion that Havana is a trip back in time but I must accept that this moment is one such trip.

My brother had been to Havana several times prior and had scoped out a cheap way to eat. The common people can not afford to participate in the tourist economy so they obviously have food sources that are not so obvious to outsiders. There are unmarked diners with long counters in front of which are long rows of multi-colored spinning soda fountain stools. There’s really not a menu. Absolutely delicious yet simply prepared pork and onions over white rice seems to be the only entree offered but at a cost of about the equivalent of fifty U.S. cents. The only drink available is an orange sugar water thirst placation that’s presented in a clear plastic tube the likes from which I’m used to seeing kids and astronauts drink. This scenario introduces us to the challenge of hanging with the peeps.  If one pays in tourist money (CUC), one is likely receive change back calculated one to one in people’s money (CUP). This is a scam. The actual exchange rate is not one to one, it’s really more like 25 units of people’s money to one unit of tourist money. I’m sure if one is adept enough in Spanish to debate the issue things fair out but in my case the wait staff feigned lack of comprehension of my grievance and kept me closer to one to one. Not having properly exchanged any of our outside money to people’s money we sacrificed the smallest tourist bill possible and ate off the people’s money change for the rest of the week.

If one pays in tourist money (CUC), one is likely receive change back calculated one to one in people’s money (CUP). This is a scam. The actual exchange rate is not one to one, it’s really more like 25 units of people’s money to one unit of tourist money. I’m sure if one is adept enough in Spanish to debate the issue things fair out but in my case the wait staff feigned lack of comprehension of my grievance and kept me closer to one to one. Not having properly exchanged any of our outside money to people’s money we sacrificed the smallest tourist bill possible and ate off the people’s money change for the rest of the week.

I venture often to the neighborhood of Vedado for I’ve learned that it’s the epicenter of Havana’s modern art scene. I hail the quintessential late forties and early fifties-era American-made taxis avoiding the fancier buff-glossy ones as they seem to command hi gher fares. The cabs have no meters and no standard transportation tariffs. You’d best make your deal before you close the cab door to seal yourself into a ride back in time. No matter how one travels we all pay for the aesthetic character that the nostalgic cabs contribute by breathing the excessive pollution that they contribute as well. The world is well aware that the old car thing is a big component of the Havana mystique. Not to discount the Cubans’ admirable resourcefulness, I wonder whether the old car phenomenon is at its core an issue of pride at marking a point in time when they kicked the Americans out. It also occurs to me by consulting pre-Castro era photos that many of these classic American cars are probably, along with the commandeered mansions, the spoils of the revolution.

gher fares. The cabs have no meters and no standard transportation tariffs. You’d best make your deal before you close the cab door to seal yourself into a ride back in time. No matter how one travels we all pay for the aesthetic character that the nostalgic cabs contribute by breathing the excessive pollution that they contribute as well. The world is well aware that the old car thing is a big component of the Havana mystique. Not to discount the Cubans’ admirable resourcefulness, I wonder whether the old car phenomenon is at its core an issue of pride at marking a point in time when they kicked the Americans out. It also occurs to me by consulting pre-Castro era photos that many of these classic American cars are probably, along with the commandeered mansions, the spoils of the revolution.

The fashionable nightlife I find in Vedado at The Fabrica des Artes is a puzzling contrast to the poverty that I see by day in old Havana. We arrive just before the velvet rope rations the waiting throngs who eventually wrap around the block. Inside this former factory is a fantasy world of color changing bulbs, bars, stages, movie screens and purchasable art. It’s a gallery where the Cuban elite artist class party. An art film has been the opening act for a classical quartet (Cuarteto de Cuerdas Amadeo Roldan) who perform with an unusual feel that I can’t at first identify. Their approach seems to tie Vivaldi and Astor Piazzolla to funk and jazz. They don’t have the exactitude that New York quartets have but they play with a soul that I’ve never heard in a classical delivery. The attentive audience loves them.

I’m curious about the hip young Cubans who have come this evening to The Fabrica Des Artes, appearing affluent and dressed as if they’re in Barcelona or Soho in New York. I am surprised to see evidence of levels Cuban society, inequality if you will, that I didn’t think was in keeping with the communist concept. To my surprise, on an official art museum tour the following day I would learn from a guide that the Cuban government is not too happy about artists leaving for greener and more lucrative pastures in New York and elsewhere. Therefore the Cuban artists who remain are allowed to sell their wares in the tourist economy and prosper beyond the commoners. I am told that the government considers artists “elite” in Cuban society. I clarify that elite in the Cuban sense means “preferred or privileged” and the description does not infer wealth. I would learn upon my return to New York that the privilege about which I am so curious can be a factor of connection with either the military or the government, often through family. The modern Cuban art in The Fabrica des Artes has a street edge to it.  For that matter, the passion and technique exemplified in some of the actual street art, essentially graffiti that I see along The Paseo del Prado, deserves wall space in the world’s best museums. I sense political innuendo and suppose that prohibited boundaries are being pushed. Also, whereas pornography is prohibited by the government, creative nudity in art seems to be a tolerated device. I’m relieved that the heavy hand of censorship has loosened its grip.

For that matter, the passion and technique exemplified in some of the actual street art, essentially graffiti that I see along The Paseo del Prado, deserves wall space in the world’s best museums. I sense political innuendo and suppose that prohibited boundaries are being pushed. Also, whereas pornography is prohibited by the government, creative nudity in art seems to be a tolerated device. I’m relieved that the heavy hand of censorship has loosened its grip.

I was entertained and informed even before The Rolling Stones en Cuba show began. To accommodate the waste management needs of the thousands waiting to enter the Ciudad Deportiva main gate, a single metal closet of sorts with no floor nor seat was positioned directly over a street gutter sewer drain to serve as an outhouse.  Once inside the fairgrounds, I counted only four proper red plastic Port-A-Lets waiting for the anticipated multitudes. My brother and I have arrived at 2pm to secure a good view for the concert that’s to start at 8pm. All afternoon giant screens play Stones videos. I wonder if the crew is attempting to prep a populace that’s not familiar with the live repertoire that’s to follow. An hour before the show the music videos stop and a classic rock audio-only mix takes over. All manner of riff-rock seems to connect. The crowd goes crazy to Smoke On The Water which is eclipsed only by AC/DC’s Highway To Hell that incites cheers, singalong and ubiquitous head bobbing. Lights out. Showtime. Thousands of periscoping cell phones prepare to film the historic event. When Keith Richards grips his green Telecaster to start the show with Jumping Jack Flash, what looks to be balloons, take flight and I learn how free healthcare and partying intertwine.

Once inside the fairgrounds, I counted only four proper red plastic Port-A-Lets waiting for the anticipated multitudes. My brother and I have arrived at 2pm to secure a good view for the concert that’s to start at 8pm. All afternoon giant screens play Stones videos. I wonder if the crew is attempting to prep a populace that’s not familiar with the live repertoire that’s to follow. An hour before the show the music videos stop and a classic rock audio-only mix takes over. All manner of riff-rock seems to connect. The crowd goes crazy to Smoke On The Water which is eclipsed only by AC/DC’s Highway To Hell that incites cheers, singalong and ubiquitous head bobbing. Lights out. Showtime. Thousands of periscoping cell phones prepare to film the historic event. When Keith Richards grips his green Telecaster to start the show with Jumping Jack Flash, what looks to be balloons, take flight and I learn how free healthcare and partying intertwine.  Young Cuban girls had been busy just before nightfall inflating condoms to use as a message in a bottle of sorts by delicately writing on the protective membrane with just enough nail polish to avoid dissolving it and the resultant pop. Fast forward to the encore that in truth the Cubans didn’t earn but not because they didn’t like the show. After Brown Sugar the band takes the expected bows and walks off. The crowd seems to accept that it’s all over. The show has been stellar, henceforth the applause should be deafening. I wonder if in the communist society, people are simply not used to asking for more than their allotted amounts. Freshly shirted, the band comes out anyway. I wonder how they knew that I Can’t Get No Satisfaction, the encore’s second and final number, would be the crowd’s concert favorite.

Young Cuban girls had been busy just before nightfall inflating condoms to use as a message in a bottle of sorts by delicately writing on the protective membrane with just enough nail polish to avoid dissolving it and the resultant pop. Fast forward to the encore that in truth the Cubans didn’t earn but not because they didn’t like the show. After Brown Sugar the band takes the expected bows and walks off. The crowd seems to accept that it’s all over. The show has been stellar, henceforth the applause should be deafening. I wonder if in the communist society, people are simply not used to asking for more than their allotted amounts. Freshly shirted, the band comes out anyway. I wonder how they knew that I Can’t Get No Satisfaction, the encore’s second and final number, would be the crowd’s concert favorite.  The crowd of at least a half-million had filed in all throughout the day but now everybody needs to leave at the same time. What’s the mass transit plan? Busses, although ready and waiting, are useless because they face away from where the crowd needs to go. The busses can’t turn around on the main street because the exodus is clogging said street. That said, everyone seems happy. If this scene was taking place in New York people would be pushing and shoving to hail the few available taxis. Miraculously my brother finds a cab that was exiting a side street. Hundreds needed a ride but the driver charges us the normal fare. I had prepared myself for a two hour walk back to old Havana even though the soles of my dress shoes are separating from the tops and my feet have already blistered from the previous three days on the cobblestones. This is one of many moments on the trip wherein I see the positive side of the communist reality and in this moment I am also disappointed that a commonly accepted aspect of capitalism is greed.

The crowd of at least a half-million had filed in all throughout the day but now everybody needs to leave at the same time. What’s the mass transit plan? Busses, although ready and waiting, are useless because they face away from where the crowd needs to go. The busses can’t turn around on the main street because the exodus is clogging said street. That said, everyone seems happy. If this scene was taking place in New York people would be pushing and shoving to hail the few available taxis. Miraculously my brother finds a cab that was exiting a side street. Hundreds needed a ride but the driver charges us the normal fare. I had prepared myself for a two hour walk back to old Havana even though the soles of my dress shoes are separating from the tops and my feet have already blistered from the previous three days on the cobblestones. This is one of many moments on the trip wherein I see the positive side of the communist reality and in this moment I am also disappointed that a commonly accepted aspect of capitalism is greed.

With a cup of strong coffee and my minimally adorned trusty Guild Starfire that I call Roadkill, I‘ve been practicing every morning in the granite lobby of my casa particular at 51 Malecón. By consequence of the echoes of my public warm-ups, a permanent building resident who’s fifth violin chair in the Sinfónica Nacional invites me to a weekend concert. I’m touched to be allowed to ride to Teatro Nacional de Cuba on the government bus with other orchestra members. The concrete hall is quintessential Latin-American modern.  The tall glass lobby has an open, Dwell Magazine sort of feel. The facility is pleasant to be in yet it’s functional and basic. I notice aesthetic details that would never have passed muster in New York. For instance a marvelous Picasso-esque scratched and painted concrete sculpture spans the entire auditorium foyer but the carpet on the conductor’s platform has separated exposing the plywood box. The austere concrete floor of the auditorium needs a once over but I’m probably the only one who’s even thinking about that sort of thing. Classical music in the U.S. seems to go hand in hand with pretense, especially at concert of comparable magnitude, but refreshingly there is no haughtiness in the air. Only the soloist, Yanet Campbell Secades seems to hold herself in a different way – elegantly so as to say “I’m special” but not to exude the air of “I’m better”.

The tall glass lobby has an open, Dwell Magazine sort of feel. The facility is pleasant to be in yet it’s functional and basic. I notice aesthetic details that would never have passed muster in New York. For instance a marvelous Picasso-esque scratched and painted concrete sculpture spans the entire auditorium foyer but the carpet on the conductor’s platform has separated exposing the plywood box. The austere concrete floor of the auditorium needs a once over but I’m probably the only one who’s even thinking about that sort of thing. Classical music in the U.S. seems to go hand in hand with pretense, especially at concert of comparable magnitude, but refreshingly there is no haughtiness in the air. Only the soloist, Yanet Campbell Secades seems to hold herself in a different way – elegantly so as to say “I’m special” but not to exude the air of “I’m better”.  She renders a perfect, riveting performance of Tchaikovsky’s’ Violin Concerto in D Major op 35. In between movements, my host, shades his eyes from the stage lights and looks for me. I’m touched by his hospitality and wonder how many years would I have to know a musician in New York before he or she would feel comfortable inviting me, in this case a complete stranger (albeit with qualifications) backstage at Lincoln Center. The functionality of presenting the music, less than the propriety of it have been the order of this day and I feel that my relationship to music has been reset for the better. Having observed the positive relationship between the Cuban government and the arts seems to contradict, again, my American prejudice against the Cuban/communist reality.

She renders a perfect, riveting performance of Tchaikovsky’s’ Violin Concerto in D Major op 35. In between movements, my host, shades his eyes from the stage lights and looks for me. I’m touched by his hospitality and wonder how many years would I have to know a musician in New York before he or she would feel comfortable inviting me, in this case a complete stranger (albeit with qualifications) backstage at Lincoln Center. The functionality of presenting the music, less than the propriety of it have been the order of this day and I feel that my relationship to music has been reset for the better. Having observed the positive relationship between the Cuban government and the arts seems to contradict, again, my American prejudice against the Cuban/communist reality.

I spend my last few hours in town at Le Gran Teatro de la Habana.  The day before my arrival, President Obama had given a speech in this building – a classic multi-tiered European style opera house. There is no other building in town as elegant nor as impeccably maintained. I suspect this magnificent building was never allowed to fall from grace while so many of its neighbors have been left to the mercy of the elements. I couldn’t elicit a straight answer from anyone on Havana soil as to why this was so. Segovia, Josephine Baker, Rachmaninoff had all played there. A Cuban friend in New York would later suggest that before the internet, The Grand’s stage, via traveling performers, was one of the only portals that Cuba had to through which to meet the rest of the world. His opinion was that by prioritizing the maintenance of this building, a positive impression would circulate amongst the world-class performers who graced the stage.

The day before my arrival, President Obama had given a speech in this building – a classic multi-tiered European style opera house. There is no other building in town as elegant nor as impeccably maintained. I suspect this magnificent building was never allowed to fall from grace while so many of its neighbors have been left to the mercy of the elements. I couldn’t elicit a straight answer from anyone on Havana soil as to why this was so. Segovia, Josephine Baker, Rachmaninoff had all played there. A Cuban friend in New York would later suggest that before the internet, The Grand’s stage, via traveling performers, was one of the only portals that Cuba had to through which to meet the rest of the world. His opinion was that by prioritizing the maintenance of this building, a positive impression would circulate amongst the world-class performers who graced the stage.

Summary.

As to the arts, The Cuban music and Cuban painting that I have experienced on this trip deliver soul with technique, and passion with complexity in a way that feels right to my senses. Socio-politically I remain a bit puzzled by the concept of the imminent commercial invasion of Cuba by Americans. Many of the paintings at Havana’s impressive modern art galleries express understandable concern for the impending American presence represented by archetypical golden arches and the familiar white cursive cola font but I don’t foresee the golden arches on The Malecón anytime soon.

It just doesn’t seem that Cuba’s close to ready in terms of infrastructure preparedness, not the least of which is a trickling internet feed. In theory I see opportunity in getting Cuba up to speed and to my eyes what Havana needs foremost is reconstruction much like the U.S. south needed after The War Between The States. That said, who’s going to pay for it?

How can our capitalistic business model coexist with the Cuban system? At its essence, capitalism depends on the individual wanting to buy things in order to better one’s life. Given that the common Cuban person has a cap on income at about $20 a month what therefore is the possibility to better one’s life, by the capitalistic standard? You Can’t Always Get What You Want, the first song of The Stones’ encore seems perfectly appropriate as the soundtrack to this quandary. As I see it, if American businesses start popping up, only the tourists and all manner of elites would be their customers. To me, this sounds ironically like the set up for a Batista era phenomenon all over again. Furthermore given that the Cuban government maintains at least a 51% stake ownership of every business, what becomes of the remaining 49%, since business owners, being normal Cuban citizens, are not, as I understand it, allowed to accumulate personal wealth beyond their needs? Will Starbucks come to Cuba like The Rolling Stones did and give it away? I doubt it. That said, investors from other countries must be figuring a way to work with the system. I came upon a hip outdoor cafe along The Malecón that has a contemporary Arab vibe and I enjoyed a gourmet meal at the retro Soviet restaurant called Nasdarvoie.

I saw no evidence in galleries and on street art that cautious creatives are bracing for what I believe to be the most predictable American threat of all. For it is one that they do not yet know – the enlarged American monster in fresh white jogging shoes. It is in advance of such wobbling ambassadors that I am most grateful that have I visited when I have. How out of place the complaining herd shall be in the face of ubiquitous poverty, deteriorating classic architecture, broken sidewalks and archaic infrastructure that create ironic character in Habana Vieja.

People describe contemporary Cuba as a trip back in time. This implies that everything’s the same as it was in the Fifties. It is not. I saw a Cuba 55 years beyond its glory days and in a state of neglect, managing well in terms of the arts, culture, free healthcare, free quality education and survival level provisions for the people etc. but maybe not so well in terms of modern infrastructure. Perhaps a Fidel or Che faithful would say that current Cuba is what glory looks like when you evict an oppressor. Either way, if your world view is that The United States is the template upon which all else should be based, it might be best to stay out of Cuba.

I must admit that I wanted to kiss the ground at J.F.K. upon my return and conversely I’m sure that all of Cuba is relieved to no longer endure my pitiful Spanish. I never got sick from the tap water but I didn’t take many chances in that department anyway because oddly enough, glass bottled Italian Acqua Panna water (referred to only as “panna”) is available everywhere. The car exhaust pollution was the most undesirable aspect of the Havana experience. I wonder if the fumes helped the cold that I caught while there turn into bronchitis.

I came expecting a wonderland of color, cracks and patina and there is that. But unlike in New Orleans, similarly ravaged by time and weather, where you know everybody just kind of wants things to look and stay that way; I don’t feel this is the case in Havana. It’s not OK but people deal and admirably so.

The Cuban people I met seemed alarmingly warm and sincere. Whereas the musicians I met seemed a little restless and resigned with an air of melancholy off stage, they awakened infectiously when they performed. Furthermore, I caught nary a hint of resentment especially knowing that it is popular to bundle blame for current economic shortcomings on the American embargo referred to as the “blockade”.

Havana would probably be better off if I returned with some power tools and stucco to lend a hand but I have reason to believe that my swampy Florida guitar style might mix well with Cuban rhythms. To that end, I hope to return to The Havana Jazz Festival in December and do my meager part to exemplify why we all might want to find a way to make peace, find a new way to do business and be helpful neighbors.

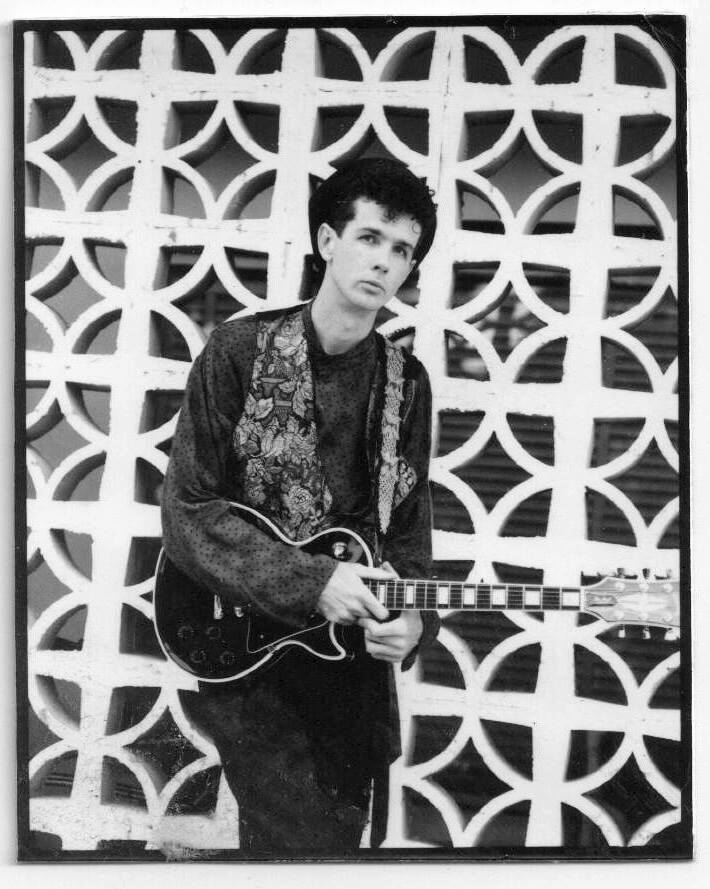

For ten years, musician and writer Walter Parks toured the world and recorded as sideman/guitarist to Woodstock legend Richie Havens. Originally from Jacksonville, Florida, Parks now resides in Jersey City, New Jersey. His solo touring show is called Swamp By Chandelier and he leads a neo-southern rock trio called Swamp Cabbage.

in from time to time during tracking and offered serious useful advice. We were recording the day Butch got word that Gregg wanted to get the band together. Butch was elated, for relief of the pressures of studio ownership seemed at hand.

in from time to time during tracking and offered serious useful advice. We were recording the day Butch got word that Gregg wanted to get the band together. Butch was elated, for relief of the pressures of studio ownership seemed at hand.

to collapse and remain unusable. There are no caution cones at the edge of gaping sidewalk holes into which the inattentive can fall. Having been raised by an architect, Old Havana creates in me a foundational level of anxiety that I will never shake during my weeklong visit.

to collapse and remain unusable. There are no caution cones at the edge of gaping sidewalk holes into which the inattentive can fall. Having been raised by an architect, Old Havana creates in me a foundational level of anxiety that I will never shake during my weeklong visit. A merchant power pedals the dead weight of an entire gutted and skin-steamed pig that’s splayed on the bike’s rear cargo shelf. A man in a wife-beater tosses a live rooster by its legs into a car trunk. Somewhere I hear a lamb, en route no doubt, to its execution. I find it. Sadly its limbs are tied. It travels on its side on the floor of a tricycle-taxi, sort of thing. Stray mangy dogs miraculously avoid buses and taxis. I don’t know if I can handle this for an entire week.

A merchant power pedals the dead weight of an entire gutted and skin-steamed pig that’s splayed on the bike’s rear cargo shelf. A man in a wife-beater tosses a live rooster by its legs into a car trunk. Somewhere I hear a lamb, en route no doubt, to its execution. I find it. Sadly its limbs are tied. It travels on its side on the floor of a tricycle-taxi, sort of thing. Stray mangy dogs miraculously avoid buses and taxis. I don’t know if I can handle this for an entire week.

The whole scenario seems so primitive to my American eyes at first because the modification is immediate and is done right in the street, not in some fancy workshop. The final result is not pretty but it functions and allows for the wheels of Havana, quite literally, to keep turning. I too prefer to fix things rather than throw them away because I don’t like to be wasteful. Perhaps I waste time making modifications but I feel that a society composed of individuals who are unable to repair things is vulnerable. For sure, in Havana, a repurposing mentality is borne of necessity and is not the cute arty hipster fad that it is in the U.S. I see the fix-it process all over town and I’ve come to think that keeping things running is a strong component of Cuban pride.

The whole scenario seems so primitive to my American eyes at first because the modification is immediate and is done right in the street, not in some fancy workshop. The final result is not pretty but it functions and allows for the wheels of Havana, quite literally, to keep turning. I too prefer to fix things rather than throw them away because I don’t like to be wasteful. Perhaps I waste time making modifications but I feel that a society composed of individuals who are unable to repair things is vulnerable. For sure, in Havana, a repurposing mentality is borne of necessity and is not the cute arty hipster fad that it is in the U.S. I see the fix-it process all over town and I’ve come to think that keeping things running is a strong component of Cuban pride. an musicians take very seriously. Over a cortadito in a cafe at the corner of The Malecón and Prado I enjoy hearing a simple trio of old Cuban men in customary white short sleeve pleated-front shirts playing old school boleros. They soothe in the spirit of The Buena Vista Social Club using merely the essentials – classical guitar, percussion and violin. I have issues with the popular opinion that Havana is a trip back in time but I must accept that this moment is one such trip.

an musicians take very seriously. Over a cortadito in a cafe at the corner of The Malecón and Prado I enjoy hearing a simple trio of old Cuban men in customary white short sleeve pleated-front shirts playing old school boleros. They soothe in the spirit of The Buena Vista Social Club using merely the essentials – classical guitar, percussion and violin. I have issues with the popular opinion that Havana is a trip back in time but I must accept that this moment is one such trip. If one pays in tourist money (CUC), one is likely receive change back calculated one to one in people’s money (CUP).

If one pays in tourist money (CUC), one is likely receive change back calculated one to one in people’s money (CUP).  gher fares. The cabs have no meters and no standard transportation tariffs. You’d best make your deal before you close the cab door to seal yourself into a ride back in time. No matter how one travels we all pay for the aesthetic character that the nostalgic cabs contribute by breathing the excessive pollution that they contribute as well. The world is well aware that the old car thing is a big component of the Havana mystique. Not to discount the Cubans’ admirable resourcefulness, I wonder whether the old car phenomenon is at its core an issue of pride at marking a point in time when they kicked the Americans out. It also occurs to me by consulting pre-Castro era photos that many of these classic American cars are probably, along with the commandeered mansions, the spoils of the revolution.

gher fares. The cabs have no meters and no standard transportation tariffs. You’d best make your deal before you close the cab door to seal yourself into a ride back in time. No matter how one travels we all pay for the aesthetic character that the nostalgic cabs contribute by breathing the excessive pollution that they contribute as well. The world is well aware that the old car thing is a big component of the Havana mystique. Not to discount the Cubans’ admirable resourcefulness, I wonder whether the old car phenomenon is at its core an issue of pride at marking a point in time when they kicked the Americans out. It also occurs to me by consulting pre-Castro era photos that many of these classic American cars are probably, along with the commandeered mansions, the spoils of the revolution.

For that matter, the passion and technique exemplified in some of the actual street art, essentially graffiti that I see along The Paseo del Prado, deserves wall space in the world’s best museums. I sense political innuendo and suppose that prohibited boundaries are being pushed. Also, whereas pornography is prohibited by the government, creative nudity in art seems to be a tolerated device. I’m relieved that the heavy hand of censorship has loosened its grip.

For that matter, the passion and technique exemplified in some of the actual street art, essentially graffiti that I see along The Paseo del Prado, deserves wall space in the world’s best museums. I sense political innuendo and suppose that prohibited boundaries are being pushed. Also, whereas pornography is prohibited by the government, creative nudity in art seems to be a tolerated device. I’m relieved that the heavy hand of censorship has loosened its grip. Once inside the fairgrounds, I counted only four proper red plastic Port-A-Lets waiting for the anticipated multitudes. My brother and I have arrived at 2pm to secure a good view for the concert that’s to start at 8pm. All afternoon giant screens play Stones videos. I wonder if the crew is attempting to prep a populace that’s not familiar with the live repertoire that’s to follow. An hour before the show the music videos stop and a classic rock audio-only mix takes over. All manner of riff-rock seems to connect. The crowd goes crazy to Smoke On The Water which is eclipsed only by AC/DC’s Highway To Hell that incites cheers, singalong and ubiquitous head bobbing. Lights out. Showtime. Thousands of periscoping cell phones prepare to film the historic event. When Keith Richards grips his green Telecaster to start the show with Jumping Jack Flash, what looks to be balloons, take flight and I learn how free healthcare and partying intertwine.

Once inside the fairgrounds, I counted only four proper red plastic Port-A-Lets waiting for the anticipated multitudes. My brother and I have arrived at 2pm to secure a good view for the concert that’s to start at 8pm. All afternoon giant screens play Stones videos. I wonder if the crew is attempting to prep a populace that’s not familiar with the live repertoire that’s to follow. An hour before the show the music videos stop and a classic rock audio-only mix takes over. All manner of riff-rock seems to connect. The crowd goes crazy to Smoke On The Water which is eclipsed only by AC/DC’s Highway To Hell that incites cheers, singalong and ubiquitous head bobbing. Lights out. Showtime. Thousands of periscoping cell phones prepare to film the historic event. When Keith Richards grips his green Telecaster to start the show with Jumping Jack Flash, what looks to be balloons, take flight and I learn how free healthcare and partying intertwine.  Young Cuban girls had been busy just before nightfall inflating condoms to use as a message in a bottle of sorts by delicately writing on the protective membrane with just enough nail polish to avoid dissolving it and the resultant pop. Fast forward to the encore that in truth the Cubans didn’t earn but not because they didn’t like the show. After Brown Sugar the band takes the expected bows and walks off. The crowd seems to accept that it’s all over. The show has been stellar, henceforth the applause should be deafening. I wonder if in the communist society, people are simply not used to asking for more than their allotted amounts. Freshly shirted, the band comes out anyway. I wonder how they knew that I Can’t Get No Satisfaction, the encore’s second and final number, would be the crowd’s concert favorite.

Young Cuban girls had been busy just before nightfall inflating condoms to use as a message in a bottle of sorts by delicately writing on the protective membrane with just enough nail polish to avoid dissolving it and the resultant pop. Fast forward to the encore that in truth the Cubans didn’t earn but not because they didn’t like the show. After Brown Sugar the band takes the expected bows and walks off. The crowd seems to accept that it’s all over. The show has been stellar, henceforth the applause should be deafening. I wonder if in the communist society, people are simply not used to asking for more than their allotted amounts. Freshly shirted, the band comes out anyway. I wonder how they knew that I Can’t Get No Satisfaction, the encore’s second and final number, would be the crowd’s concert favorite.  The crowd of at least a half-million had filed in all throughout the day but now everybody needs to leave at the same time. What’s the mass transit plan? Busses, although ready and waiting, are useless because they face away from where the crowd needs to go. The busses can’t turn around on the main street because the exodus is clogging said street. That said, everyone seems happy. If this scene was taking place in New York people would be pushing and shoving to hail the few available taxis. Miraculously my brother finds a cab that was exiting a side street. Hundreds needed a ride but the driver charges us the normal fare. I had prepared myself for a two hour walk back to old Havana even though the soles of my dress shoes are separating from the tops and my feet have already blistered from the previous three days on the cobblestones. This is one of many moments on the trip wherein I see the positive side of the communist reality and in this moment I am also disappointed that a commonly accepted aspect of capitalism is greed.

The crowd of at least a half-million had filed in all throughout the day but now everybody needs to leave at the same time. What’s the mass transit plan? Busses, although ready and waiting, are useless because they face away from where the crowd needs to go. The busses can’t turn around on the main street because the exodus is clogging said street. That said, everyone seems happy. If this scene was taking place in New York people would be pushing and shoving to hail the few available taxis. Miraculously my brother finds a cab that was exiting a side street. Hundreds needed a ride but the driver charges us the normal fare. I had prepared myself for a two hour walk back to old Havana even though the soles of my dress shoes are separating from the tops and my feet have already blistered from the previous three days on the cobblestones. This is one of many moments on the trip wherein I see the positive side of the communist reality and in this moment I am also disappointed that a commonly accepted aspect of capitalism is greed. The tall glass lobby has an open, Dwell Magazine sort of feel. The facility is pleasant to be in yet it’s functional and basic. I notice aesthetic details that would never have passed muster in New York. For instance a marvelous Picasso-esque scratched and painted concrete sculpture spans the entire auditorium foyer but the carpet on the conductor’s platform has separated exposing the plywood box. The austere concrete floor of the auditorium needs a once over but I’m probably the only one who’s even thinking about that sort of thing. Classical music in the U.S. seems to go hand in hand with pretense, especially at concert of comparable magnitude, but refreshingly there is no haughtiness in the air. Only the soloist, Yanet Campbell Secades seems to hold herself in a different way – elegantly so as to say “I’m special” but not to exude the air of “I’m better”.

The tall glass lobby has an open, Dwell Magazine sort of feel. The facility is pleasant to be in yet it’s functional and basic. I notice aesthetic details that would never have passed muster in New York. For instance a marvelous Picasso-esque scratched and painted concrete sculpture spans the entire auditorium foyer but the carpet on the conductor’s platform has separated exposing the plywood box. The austere concrete floor of the auditorium needs a once over but I’m probably the only one who’s even thinking about that sort of thing. Classical music in the U.S. seems to go hand in hand with pretense, especially at concert of comparable magnitude, but refreshingly there is no haughtiness in the air. Only the soloist, Yanet Campbell Secades seems to hold herself in a different way – elegantly so as to say “I’m special” but not to exude the air of “I’m better”.  She renders a perfect, riveting performance of Tchaikovsky’s’ Violin Concerto in D Major op 35. In between movements, my host, shades his eyes from the stage lights and looks for me. I’m touched by his hospitality and wonder how many years would I have to know a musician in New York before he or she would feel comfortable inviting me, in this case a complete stranger (albeit with qualifications) backstage at Lincoln Center. The functionality of presenting the music, less than the propriety of it have been the order of this day and I feel that my relationship to music has been reset for the better. Having observed the positive relationship between the Cuban government and the arts seems to contradict, again, my American prejudice against the Cuban/communist reality.

She renders a perfect, riveting performance of Tchaikovsky’s’ Violin Concerto in D Major op 35. In between movements, my host, shades his eyes from the stage lights and looks for me. I’m touched by his hospitality and wonder how many years would I have to know a musician in New York before he or she would feel comfortable inviting me, in this case a complete stranger (albeit with qualifications) backstage at Lincoln Center. The functionality of presenting the music, less than the propriety of it have been the order of this day and I feel that my relationship to music has been reset for the better. Having observed the positive relationship between the Cuban government and the arts seems to contradict, again, my American prejudice against the Cuban/communist reality. The day before my arrival, President Obama had given a speech in this building – a classic multi-tiered European style opera house. There is no other building in town as elegant nor as impeccably maintained. I suspect this magnificent building was never allowed to fall from grace while so many of its neighbors have been left to the mercy of the elements. I couldn’t elicit a straight answer from anyone on Havana soil as to why this was so. Segovia, Josephine Baker, Rachmaninoff had all played there. A Cuban friend in New York would later suggest that before the internet, The Grand’s stage, via traveling performers, was one of the only portals that Cuba had to through which to meet the rest of the world. His opinion was that by prioritizing the maintenance of this building, a positive impression would circulate amongst the world-class performers who graced the stage.

The day before my arrival, President Obama had given a speech in this building – a classic multi-tiered European style opera house. There is no other building in town as elegant nor as impeccably maintained. I suspect this magnificent building was never allowed to fall from grace while so many of its neighbors have been left to the mercy of the elements. I couldn’t elicit a straight answer from anyone on Havana soil as to why this was so. Segovia, Josephine Baker, Rachmaninoff had all played there. A Cuban friend in New York would later suggest that before the internet, The Grand’s stage, via traveling performers, was one of the only portals that Cuba had to through which to meet the rest of the world. His opinion was that by prioritizing the maintenance of this building, a positive impression would circulate amongst the world-class performers who graced the stage.

In the wisdom of my youth I was frustrated at having to play popular songs that I didn’t compose. I considered the obligation to play covers an impediment to my success, rather than to study what made these songs resonate universally with the public and allow this knowledge to influence my own writing. Fast forward 30 years, I roll up my sleeves, dig in and become “one” with the tune, and begin to understand and appreciate it on a different level.

In the wisdom of my youth I was frustrated at having to play popular songs that I didn’t compose. I considered the obligation to play covers an impediment to my success, rather than to study what made these songs resonate universally with the public and allow this knowledge to influence my own writing. Fast forward 30 years, I roll up my sleeves, dig in and become “one” with the tune, and begin to understand and appreciate it on a different level.

Bob’s an esteemed instructor from Philly who now runs a successful online teaching operation out of Las Vegas. I’m grateful to Bob but I feel like I really found the pathway to my style, years later, through watching and listening to Daniel Lanois. Observing his beautiful relationship with the instrument inspired me to stop playing with a pick. I “transitioned” in the middle of my ten years with Richie Havens. At first I was a little bit sluggish but when I finally got the hang of it, there was little sense in ever again letting a piece of plastic get between me and the guitar.

Bob’s an esteemed instructor from Philly who now runs a successful online teaching operation out of Las Vegas. I’m grateful to Bob but I feel like I really found the pathway to my style, years later, through watching and listening to Daniel Lanois. Observing his beautiful relationship with the instrument inspired me to stop playing with a pick. I “transitioned” in the middle of my ten years with Richie Havens. At first I was a little bit sluggish but when I finally got the hang of it, there was little sense in ever again letting a piece of plastic get between me and the guitar.